Last week I celebrated Mother’s Day with a rush of loving memories of my mom, and wonderful virtual visits with my grown daughter, my sweet granddaughter, my sister, and two favorite nieces. On occasions like this, I am filled with love, and gratitude for my deep familial bonds, but I also grapple with questions about my family history and the legacy of breast cancer that I may leave my family.

I have been diagnosed with breast cancer four times over the past twenty years. I was 48 at my first diagnosis, which is considered a young age. I had three tumors clustered together. My second cancer, on the opposite breast, triggered a recommendation from my doctor to undergo genetic testing to look for mutations of genes associated with a high risk for breast cancer. In my case, all the genetic test results have been negative, which means no known breast cancer gene mutations were found. I even underwent a gene panel for all types of hereditary cancers and those results were negative too. It’s important to know that research estimates that only 5-10% of breast cancer cases are caused by changes in genes or “mutations” that are passed on from a parent and in turn, can be passed on to children.

I am a Patient and Research Advocate who helps guide WISDOM and ensures that participants have a positive experience while on the study. So, I thought it might be helpful to share my story and questions on the role of family history and genetic testing in breast cancer, to get some answers for all of us.

I have a sister who is just 18 months older than me who has, thank goodness, not had breast cancer. In fact, none of my close (first degree) relatives have ever had breast cancer. However, my maternal grandfather’s sister had breast cancer, then her daughter was diagnosed with breast cancer on both breasts, and then her daughter (my 2nd cousin) was diagnosed with breast cancer as a young woman. So, does this side of my family have a familial breast cancer gene? And what does this mean about the risk facing my adult daughter, my 3-year-old granddaughter, my sister and her two daughters? Breast cancer risk tools and questionnaires always ask about cancer in first degree relatives (mother, father, siblings, children) but do later degree relatives (cousins, aunts/uncles, grandparents, etc.) count at all when looking at family history and its potential to cause breast cancer for you?

We asked WISDOM’s Genetic Counselor, Lisa Madlensky, PhD, CGC of UC San Diego to weigh in on this question and others. Here, she provides some clarity to the evolving field of Cancer Genetics.

Diane: I understand that all cancers are caused by changes in genes – are all these mutations passed down from family? If not, where do they come from?

Lisa: It’s true that all cancers are the result of mutations (changes) to genes. But most of these changes are not passed down from your family- instead, these changes are acquired in the cells of our body over the course of a lifetime. In fact, the vast majority of cancers are known as “sporadic” meaning that there is not a clear hereditary cause. Instead, they are caused by the accumulation of genetic mutations in our cells that occur through the aging process, as well as from exposures to things we encounter in our lives. For example, high levels of sun exposure can add to the accumulation of mutations in our skin cells and may increase the chance for a melanoma to develop. Again, most cancers are not caused by genetic mutations passed down from your family. But the answer isn’t that simple. You see, scientists are now learning a lot about Polygenic Risk (how collections of small genetic variations inherited from our ancestors may be protective against our ongoing accumulation of mutations or may make us more susceptible to them). For example, genetic variation from person to person may impact how we metabolize various cancer-causing substances, or repair cell damage, or influence our health behaviors like diet and exercise patterns. The science moves quickly, and we are discovering more about how these smaller genetic variants might work, in part through participation in research studies like WISDOM!

Diane: Do only first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, and children) count when it comes to who in your family may impact your risk for breast cancer, or do all relatives with breast cancer have an impact on whether we are at risk?

Lisa: Similar to the answer above, it’s not clear cut, but as a rule of thumb the closer the degree of the relative with cancer, the more genes you share, and so there is a higher chance of having a shared genetic susceptibility to cancer. In general, cancer in a first degree relative is a stronger indicator of possible cancer risk than in a second degree relative (grandparents, aunts/uncles, nieces/nephews), and so on. I also urge people to not discount the father’s side of the family when it comes to considering risk for breast cancer- half of our genes come from our mother, and half from our father.

Diane: How about the issue of number of relatives? if there’s a lot of breast cancer on the limbs of your family tree but a first degree relative doesn’t have it, what does that mean? Like in my case, with my great aunt, my aunt (her daughter) and my second cousin (her daughter), could there be a particular family gene that’s mutated?

Lisa: When we evaluate a family history, we ask a lot of questions about the relatives with cancer, but also those without. For example, if you come from a large family and you have lots of female relatives who have lived to an old age and there is only one relative with cancer, then it is unlikely that there is a high-risk mutation running through the family. But if you have a small family, or a family with very few female relatives, then it isn’t always possible to get an accurate idea of risk. We see this sometimes with women who have tested positive for a BRCA gene mutation and are surprised because they are the first person in the family to have cancer—often they inherited their mutation from their father and didn’t have any female relatives on their father’s side of the family.

There can also be a component related to where your ancestors came from. For example, women who have Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry have a 1 in 40 chance of having a BRCA mutation. This is about 10 times higher than the rate of mutations in the general population.

Diane: If you have a mutation on a gene that is associated with risk for breast cancer does that mean you are going to get it or that your children will?

Lisa: What we know today is that there are a handful of genes that are clearly associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (including the BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, P53, PTEN, CHEK2, CDH1, PALB2, and STK11 genes that are tested in the Wisdom Study). If you learn you have a genetic mutation on one of those genes it does NOT mean that you are going to get breast cancer nor that your children will get it. Rather, a genetic mutation on a high-risk gene puts you at higher risk for developing cancer. And some of those genes confer a much higher risk than others. On average, a woman with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutation has a greatly elevated chance of getting breast cancer by age 80 (around 40-80% depending on genetic and non-genetic factors) whereas one of the common CHEK2 gene mutations doubles the risk of breast cancer (so about a 25% lifetime risk, although there is a wide range of breast cancer risks with this gene that depend on other factors like family history and polygenic risk). It is important to remember that similarly to having factors that put us at risk for developing cancers, there are protective factors that can help prevent us from developing cancers.

Diane: Why does my daughter have a greater than average risk of breast cancer, even though I tested negative for hereditary cancer? And are all my relatives at greater risk than average?

Lisa: Most people with breast cancer will have negative genetic testing, meaning there isn’t a single inherited gene mutation that caused their cancer. However, because of polygenic risk (those small variations in our genes that can influence risk), as well as non-genetic factors that tend to be similar within families like environmental exposures or diet or alcohol patterns, multiple studies have found that having a close relative with breast cancer is a risk factor even when a mutation in one of the major genes is not present. However, it’s important to remember that “increased risk” doesn’t always mean the same as “high risk” – for example increased risk might mean an increase of one or two percentage points spread out over an entire lifetime. Each woman will have personal risk factors and personal protective factors that contribute to her individual level of risk.

Diane: I’ve been told that age at the time of a cancer diagnosis is associated with a risk of your close relatives getting breast cancer. So, my being first diagnosed at the age of 48 puts my daughter at greater risk than if I had first gotten breast cancer at 80. Why is that?

Lisa: In general, our genes contribute more to our risk of disease at a young age, while the aging process contributes more to our risk of disease in older age. So, for example, women with a BRCA mutation are more likely to get breast cancer before menopause, while most breast cancers that occur after menopause are not related to one specific gene- they are more likely to be the result of those accumulated mutations in cells over a lifetime that we talked about earlier. BUT it is also true that most women with premenopausal breast cancer have negative genetic testing, and there are certainly women with breast cancer later on in life who test positive on their genetic testing. So, a lot of what we hear are trends, but they may or may not apply to any individual person or family.

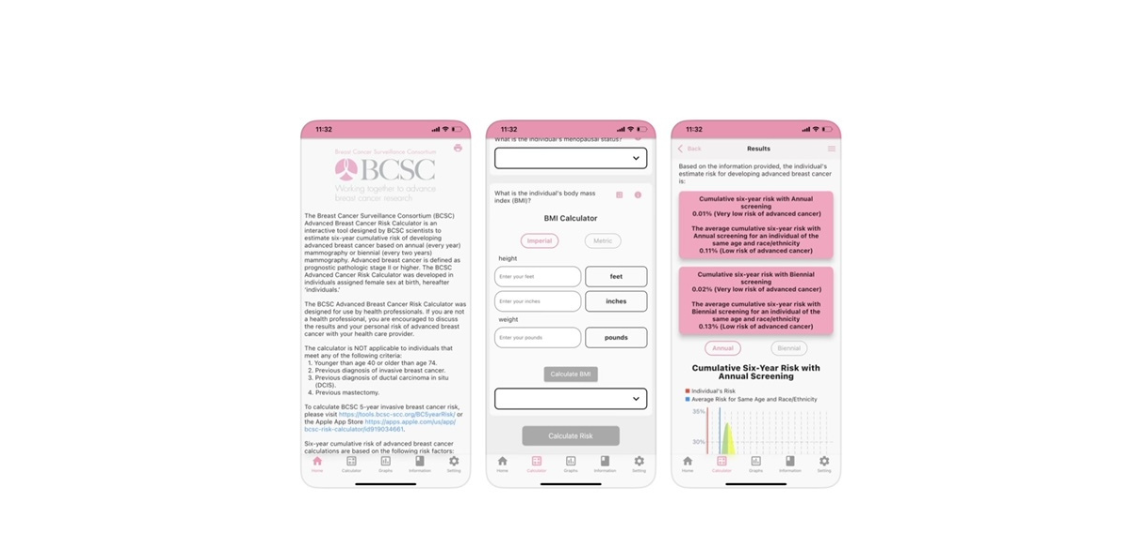

In general, if you have many relatives with breast cancer at a young age, but so far, no specific mutation has been identified in your family, we might recommend that women in the family start their screening at a younger age since we don’t yet know all there is to know about genetic and non-genetic risk. But I’m hopeful that studies like WISDOM will help to further our understanding so that we can look forward to being able to provide women with more accurate personalized assessments of their risk.

I hope that these questions and answers helped you to understand the basic elements of how your family health history impacts your (and your children’s) risk for breast cancer. There is a lot more to discuss, so we will continue to share information about breast cancer risk and how to reduce it, and we’ll keep you informed of the cutting-edge science as our clinician and researchers find the answers.

For now, here’s more information from reputable sources you can review:

- FORCE (Facing Hereditary Cancer Empowered) https://www.facingourrisk.org/portal/inherited-cancer-risk

- American Cancer Society

- Personalized Family Health Tool: An online tool from the Surgeon General that enables you to enter and track your family health information and learn your risk for certain diseases.

Written by Diane Heditsian, Founder and CEO of deClarity, and WISDOM Study Patient Advocate, with support from Lisa Madlensky, PhD, CGC, WISDOM Study Genetic Counselor and Director of the Family Cancer Genetics Program, UC San Diego Health System